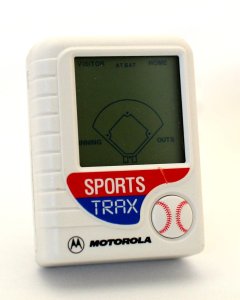

In 1994, the Toronto Blue Jays introduced a revolutionary concept: SportsTrax, a mobile device that gave you more-or-less real time updates on all games the Jays played. Using the same technology as an LCD pager, it would display runners on base and, of course, outs, inning, runs, hits and errors. If you turned the sound up, it would even cheer, boo and jeer plays as they happened. TV ads for it featuring Cito Gaston and BJ Birdy aired on TSN.

Manufactured by Motorola, it really was a cool idea. At a time when the internet was more novelty than necessity, real-time information about sporting events was hard to come by; either you watched on TV (if the game was even broadcast; most major cities only had one sports channel in those days), sat glued to the radio, or waited until the next day and read about it on the sports page.

Under the hood, SportsTrax was actually pretty primitive: a new startup called “Sports Teams Analysis Tracking Systems” (perhaps you’ve since heard of them; STATS, Inc, anyone?) hired people to watch the games, and then input what they’d just seen to Motorola’s satellite uplink.

The Blue Jays were (very) early adopters; for 149.00 you got unlimited data (Motorola estimated that it would be about 3 years ’til the little guy was outpaced by newer technologies) for the life of the device.

So why didn’t it catch on? Well, for one thing, 149.00 was a lot of money 25 years ago. I, with a young family, certainly couldn’t have justified the expense. Motorola projected sales of 50,000 in the first year; I’d be surprised if they managed 10% of that.

The other thing that happened was the NBA. Motorola wanted to bring their technology to pro basketball. When talks broke down, they went ahead anyway and, in 1996, David Stern & Co. sued.

“The National Basketball Association v. Sports Teams Analysis Tracking Systems, aka STATS, Inc.” (now more commonly referred to as NBA v. Motorola) became a landmark intellectual property rights case in American sport.

The NBA asserted that Motorola’s product constituted a live broadcast and, as such, was proprietary information, only available to licensed broadcasters (you’ve all heard the blurb during every sports broadcast).

Motorola and STATS contended that the data they were providing was just factual information, available to anyone. Blow-by-blow game accounts were available the next morning in every newspaper; SportsTrax just sped up the process.

Though a lower court granted an injunction, in 1997, the NY State 2nd Circuit appellate overturned it, finding that, “(1) Sports Trax is not a substitute for the product offered by the NBA — being at the game or watching it on television — and (2) there was no “free-riding” because STATS and Motorola expended their own resources to collect the factual information (broadcast to the public via television or radio) which they then disseminated.” In this case, SportsTrax’ primitiveness helped it survive.

Of course, by 1997, SportsTrax was pretty much obsolete, anyway. More and more families now had internet connectivity, and new TV sports channels were springing up (seemingly) every week.

The corollary here is that these initial forays into this brave new world forced sports leagues to meet new technologies and platforms head on; in 2000, Major League Baseball started Major League Baseball Advanced Media (MLBAM), to oversee all online and mobile applications. After some initial teething problems, BAM generated US$620 million in revenues for its member clubs in 2012.

That said, every time that you see a crawler showing live updates of one sport while you’re watching another, you can (indirectly) thank Motorola’s fight with the NBA.

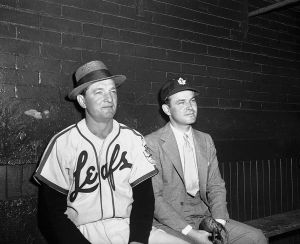

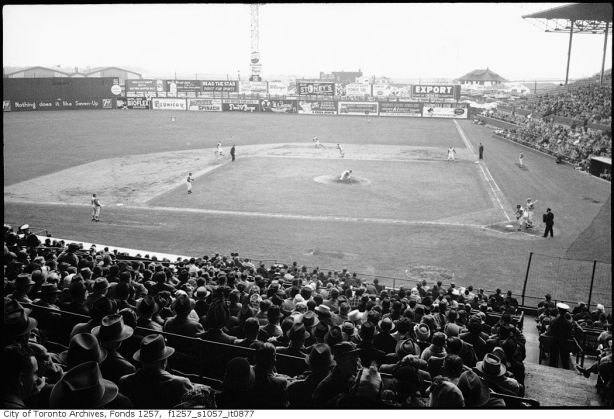

After his success in Cleveland, it was inevitable that Veeck would find his way back into Major League ownership. It was also inevitable that his ticket back in would be another fire sale; in this case, the sad-sack

After his success in Cleveland, it was inevitable that Veeck would find his way back into Major League ownership. It was also inevitable that his ticket back in would be another fire sale; in this case, the sad-sack